I don’t think I have penned a political post here before. However, it was my birthday on Friday, and I share it with the anniversary of Labour’s first full year in power, so it feels like a good time.

For context, I am and have always been politically agnostic. I read the manifestos, attempt to decipher which of the outlandish ‘promises’ might conceivably be delivered in a diluted and protracted fashion, weigh up which is best for my family, then business and then vote. I always vote.

So, this is not an ‘anti-Labour’ rant. They have proven themselves to be equally hapless as the previous administrations. In my younger days, I worked extensively with The Government from Blair to Boris, so I have witnessed first-hand the dark arts of modern politics. Never apologise is not a new mantra and never answering a question has always been the key to a successful interview. But what has changed is suitability.

Rachel Reeves has been dragged through the press over the last few days. If she received difficult news during PMQ’s she deserves our sympathy, not ridicule. I personally hope whatever the news was, it is something that does not cause her too much anguish.

I do, though, want to ask a simple question.

Why do the rules of business not apply to the people who create the rules of business?

This month, the Labour government quietly announced one of the most short-sighted acts of economic self-sabotage in recent memory.

From 22 July 2025, the minimum salary threshold for ‘new entrants’ under the UK’s Skilled Worker visa route will rise to £33,400.

For context, that figure was £20,960 just five years ago – a 59% increase. This rise is not indexed to inflation, which rose by 21.2% over the same period (figures via ONS), nor to productivity growth. It’s not part of a cohesive industrial strategy. It is, in effect, policy untethered from economic reality.

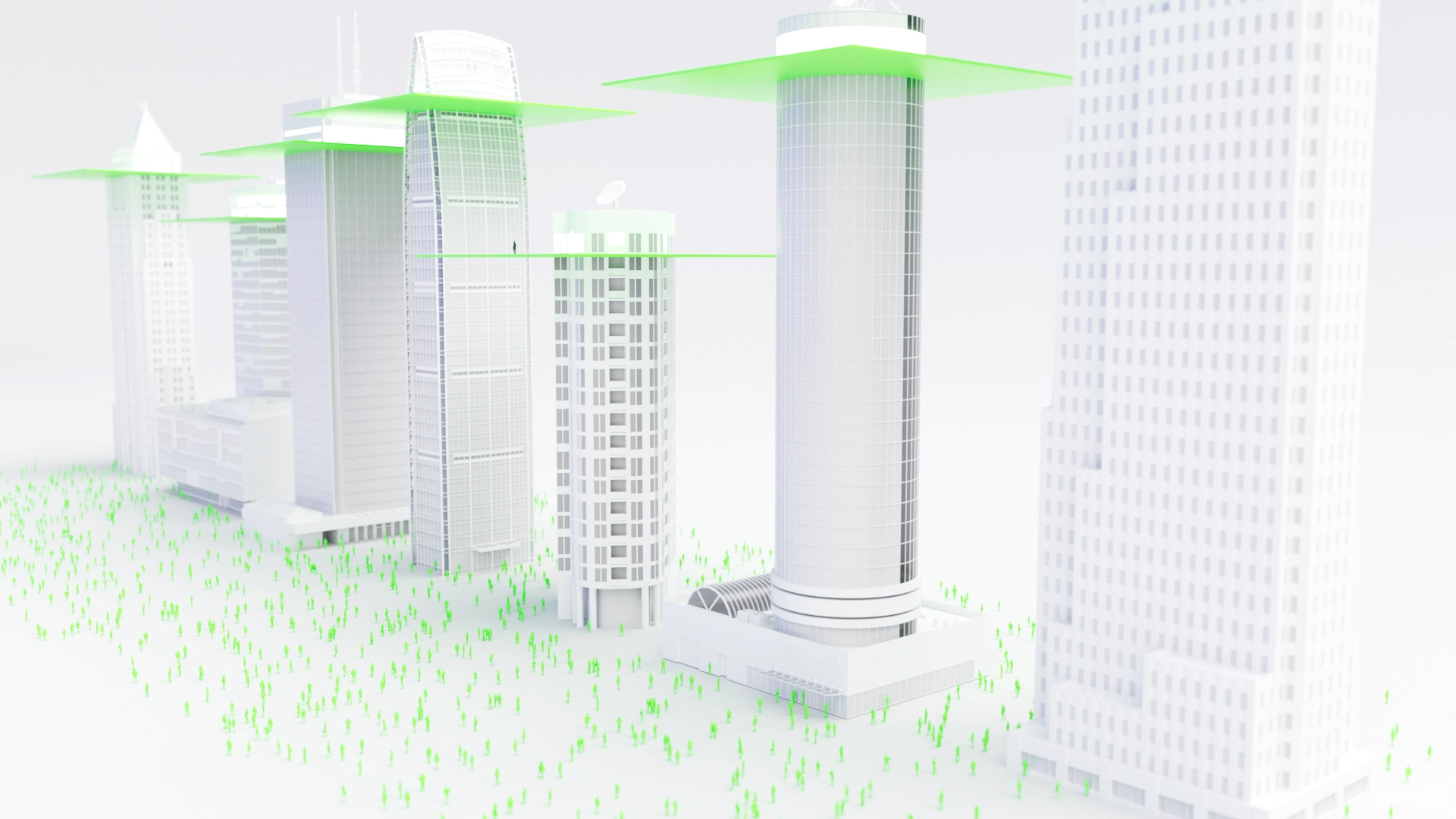

As a business that employs people on entrant visas, we have seen first-hand the value, energy and global perspectives they bring – not just to our team, but to the UK economy more broadly. This decision isn’t just bureaucratic overreach. It’s a signal. A signal that international talent is no longer welcome unless it fits a narrow, arbitrary and misaligned financial mould. Only Mitul and I were born in the UK in our entire team, the remaining talent comes from Latvia to Lithuania, Sardinia to Sweden and many more brilliant places beyond.

But the deeper issue here isn’t just the numbers. It’s the mindset behind them and my earlier question.

Why do the rules of business not apply to the people who create the rules of business?

We need to jump through hundreds of hoops to hire talent from outside the UK. We need to prove suitability, show there is not easily accessible talent already here, make sure the candidate will contribute to us and to the exchequer via taxes.

Therefore, we would rightly expect that Labour’s front bench would have requisite business experience. Right? So, how many have hired a graduate, navigated payroll during a recession, or held a position of responsibility within any kind of business at all?

According to publicly available bios, the answer is almost none.

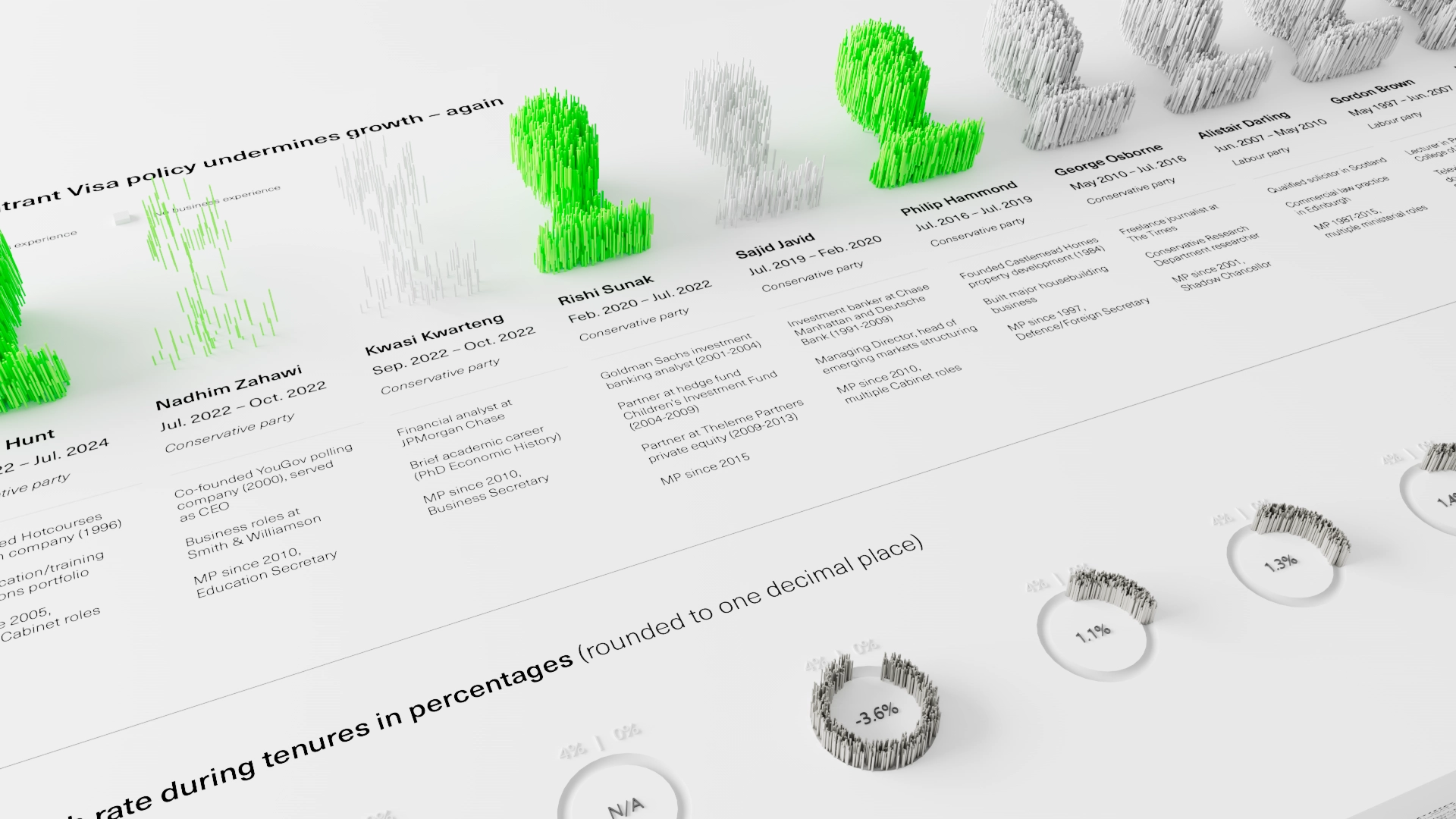

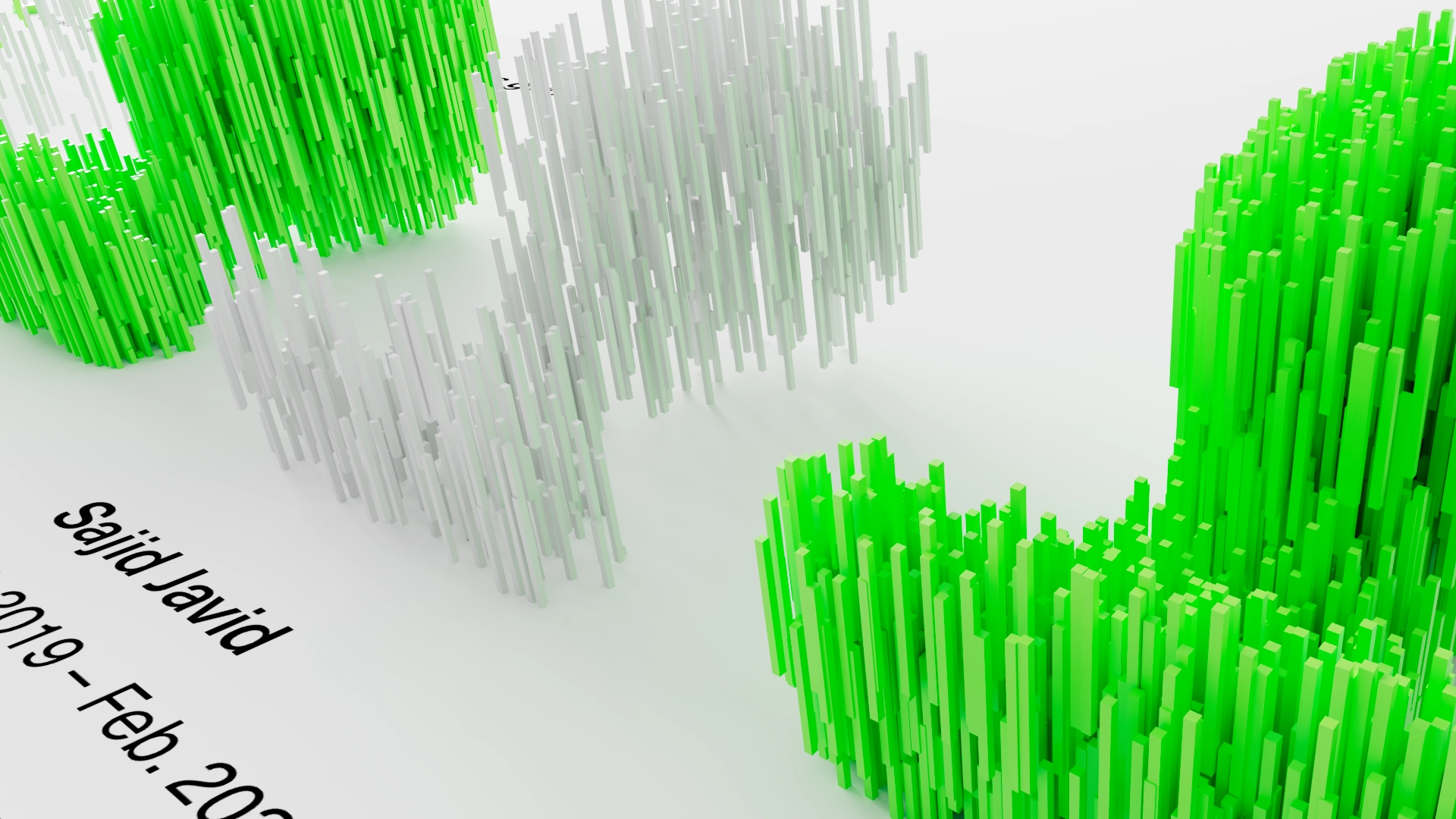

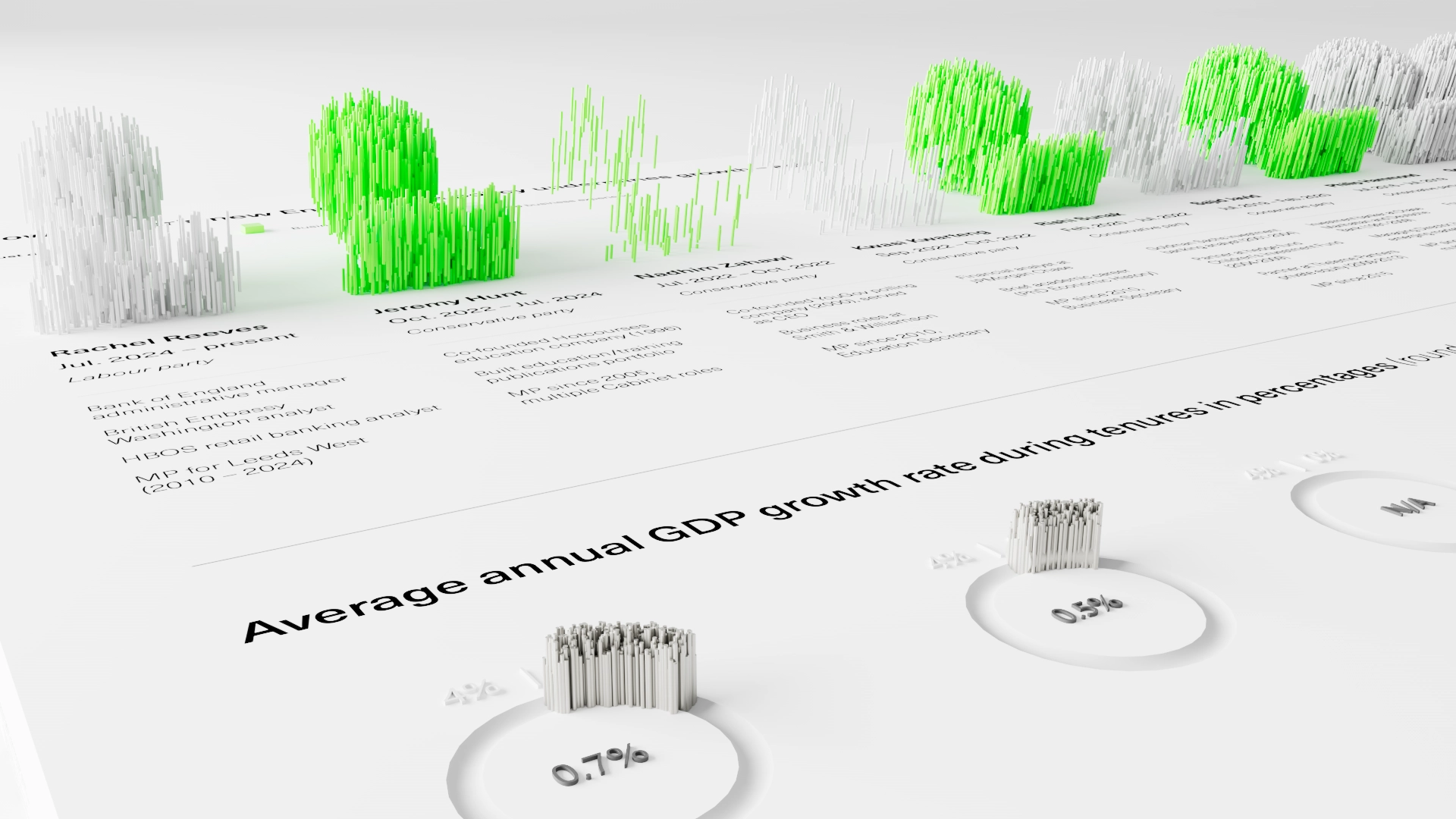

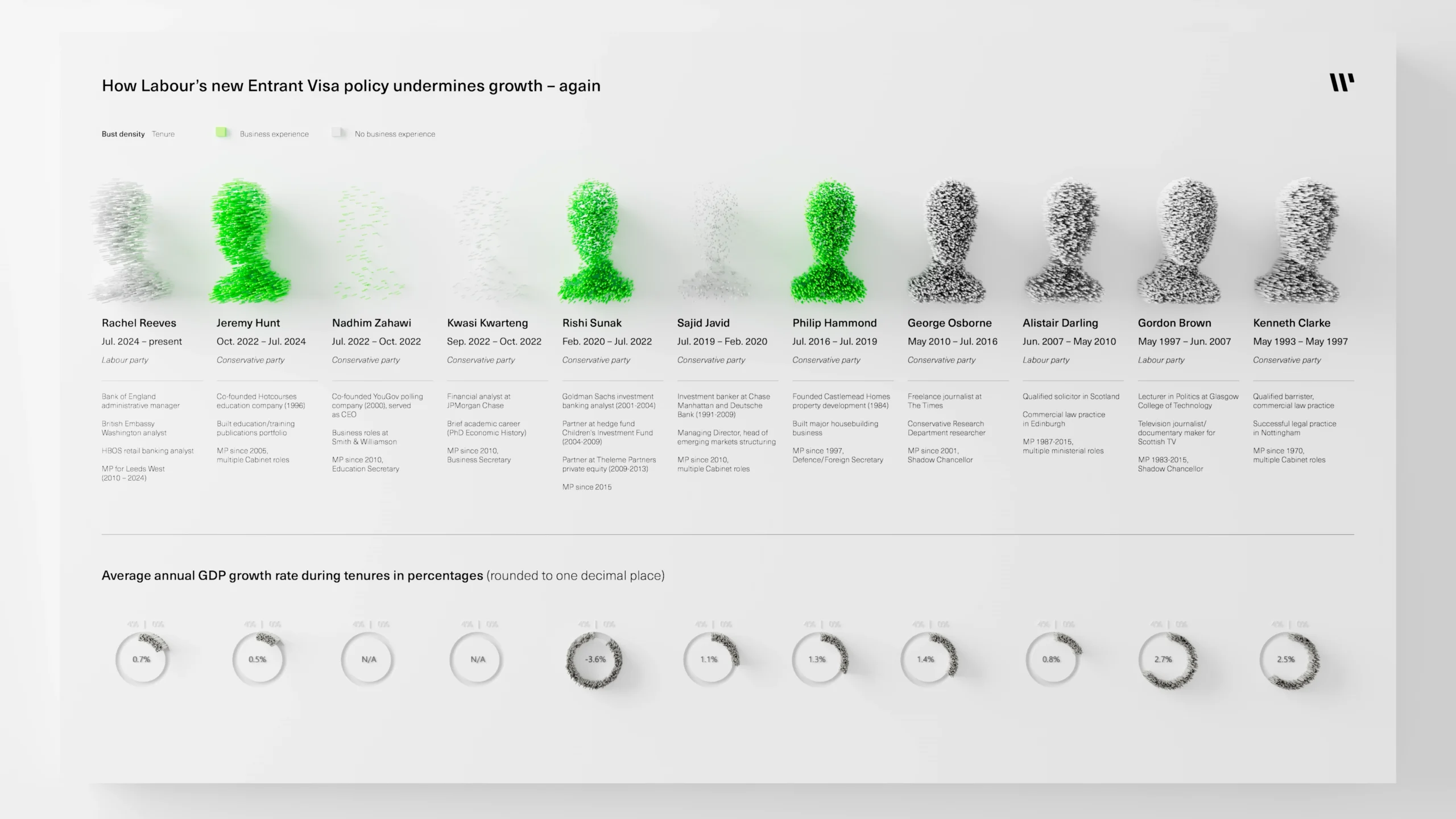

In fact, of the last ten UK Chancellors of the Exchequer, there is a worrying trend.

Jeremy Hunt was a co-Founder and Director, Nadhim Zahawi (briefly) was a Founder and CEO. Kwasi Kwarteng never ran a business himself, whilst Rishi Sunak co-Founded an investment firm. Sajid Javid was at Deutsche Bank, where he became a Managing Director and Philip Hammond co-Founded several healthcare and property businesses. George Osborne at seventh in the list, and Kenneth Clarke in tenth had zero business experience; both were career politicians. Sandwiched between them, Alistair Darling and Gordon Brown (a very nice chap, incidentally) also had no business experience at all. We now have Rachel Reeves, also with no real-world experience at all.

That means that Labour have not put anyone in this vital post with any actual experience of business since Denis Healey in 1974. And even then, his experience was hugely limited. I have not exhaustively researched further back, but arguably, there may not have been a single Labour holder of this key business role with any CV of note in the post-war era. Let that sink in.

But does it even matter? Are the people who have held the post smart? Undoubtedly, yes. But equipped to understand the delicate calculus of early-stage hiring? Unlikely. None have been in the position of having to ask: Can I take a chance on this junior? Can I justify this hire to my board (which for me means Rux, Kornelia, Karina)? Can we afford to train while we scale?

In sectors that drive economic growth – creative industries, technology, digital services, cleantech, advanced manufacturing – graduate salaries often start below £33k. Not because these jobs are low-skilled or low-impact, but because early-stage businesses are investing heavily in training, infrastructure and scale.

This isn’t unique to our business

A 2024 report by TechUK found that 46% of startups in the UK pay entry-level tech staff between £28,000 and £32,000 – well below the new threshold. Under these new rules, most early-career international hires will simply be ineligible. Not underqualified. Just unaffordable on paper.

Here is the paradox:

- We train international students at world-class universities (second only to the US)

- We encourage businesses to think and hire globally (despite Brexit)

- We then make it impossible for these students to contribute to our economy and pay taxes.

Fucking ludicrous.

This is not how competitive economies behave. Canada, Germany, the Netherlands and the UAE are all actively simplifying their visa regimes, offering fast-track residency, tax incentives and startup packages for global talent. In contrast, the UK seems determined to send the opposite message: “Thanks for studying here. Now, please leave.”

Labour claims this policy is about “protecting British jobs.” But that’s a false premise. Graduate hires are not a zero-sum game. Businesses do not hire global talent to replace domestic workers – they hire them to build capacity, expand operations and create more jobs for everyone. Just ask Mitul.

The truth? This is very poorly acted political theatre, not policy reform. Designed to look ‘tough on immigration’ while ignoring (or being unqualified to understand) the economic cost.

But trust me, the cost is real

The Centre for European Reform estimates that Brexit-related migration policies have already reduced UK GDP by 4%. Add in unfriendly post-Brexit visa policies like this one, and you compound the damage.

For every junior international employee we cannot hire, we lose not only their potential, but the growth, export value and job creation they help unlock. And everyone else loses the huge contribution they make through income tax and NI (don’t get me started on this).

As founders, directors and hiring managers, we are now having to consider:

- Should we build our next studio in Lisbon instead of London?

- Do we create another subsidiary in a friendlier market?

- Do we relocate teams to countries that actually welcome talent?

It’s frustrating. Because I want to invest here in the UK. We want to hire here. We want to grow here. But policies like this make it harder every quarter.

No one expects every politician to have run a business. But we do expect them to listen to those who have. The people who take the risks. Who hire the talent. Who build the teams. Who pay the taxes.

This isn’t about politics. It’s about growth.

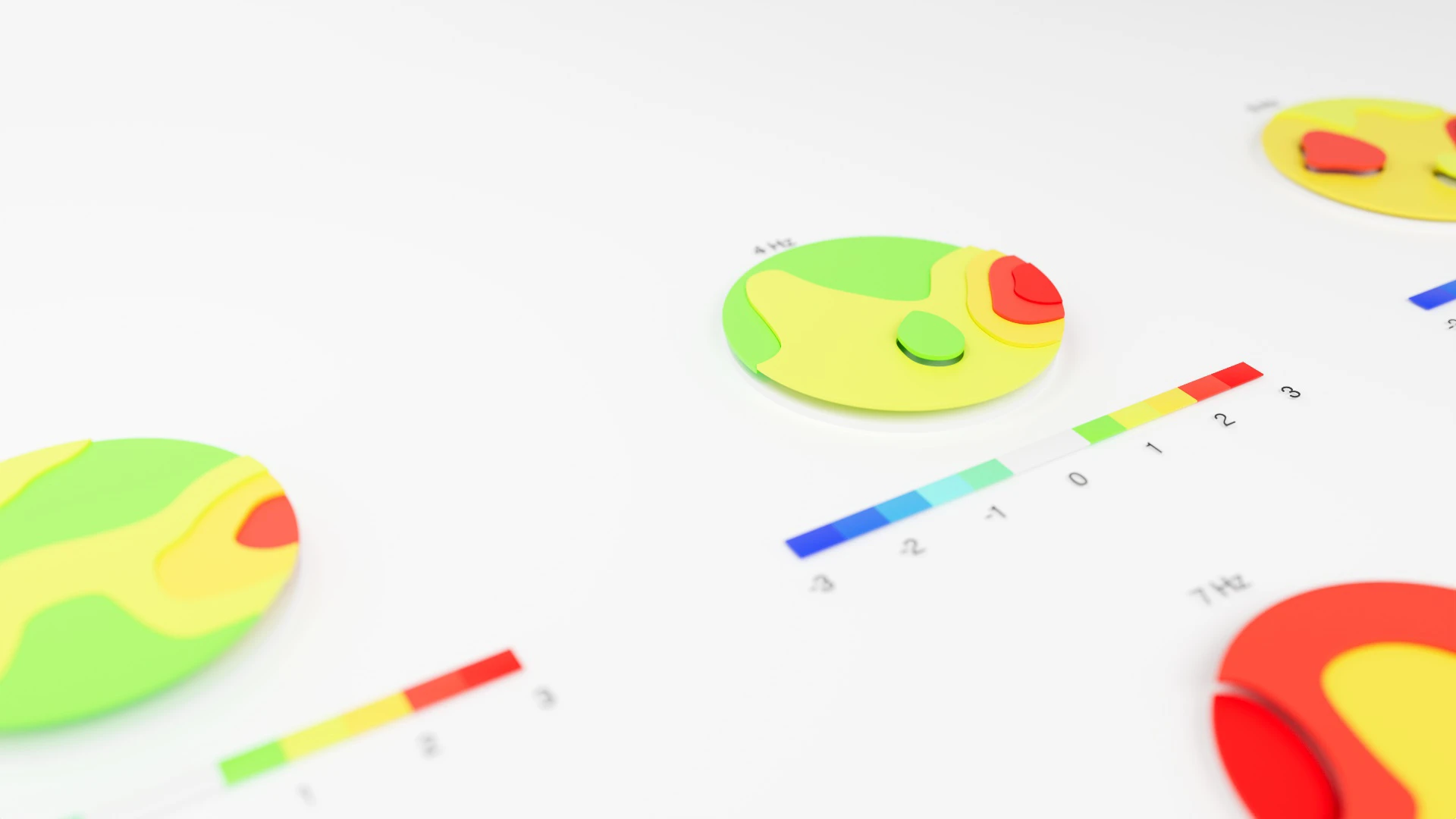

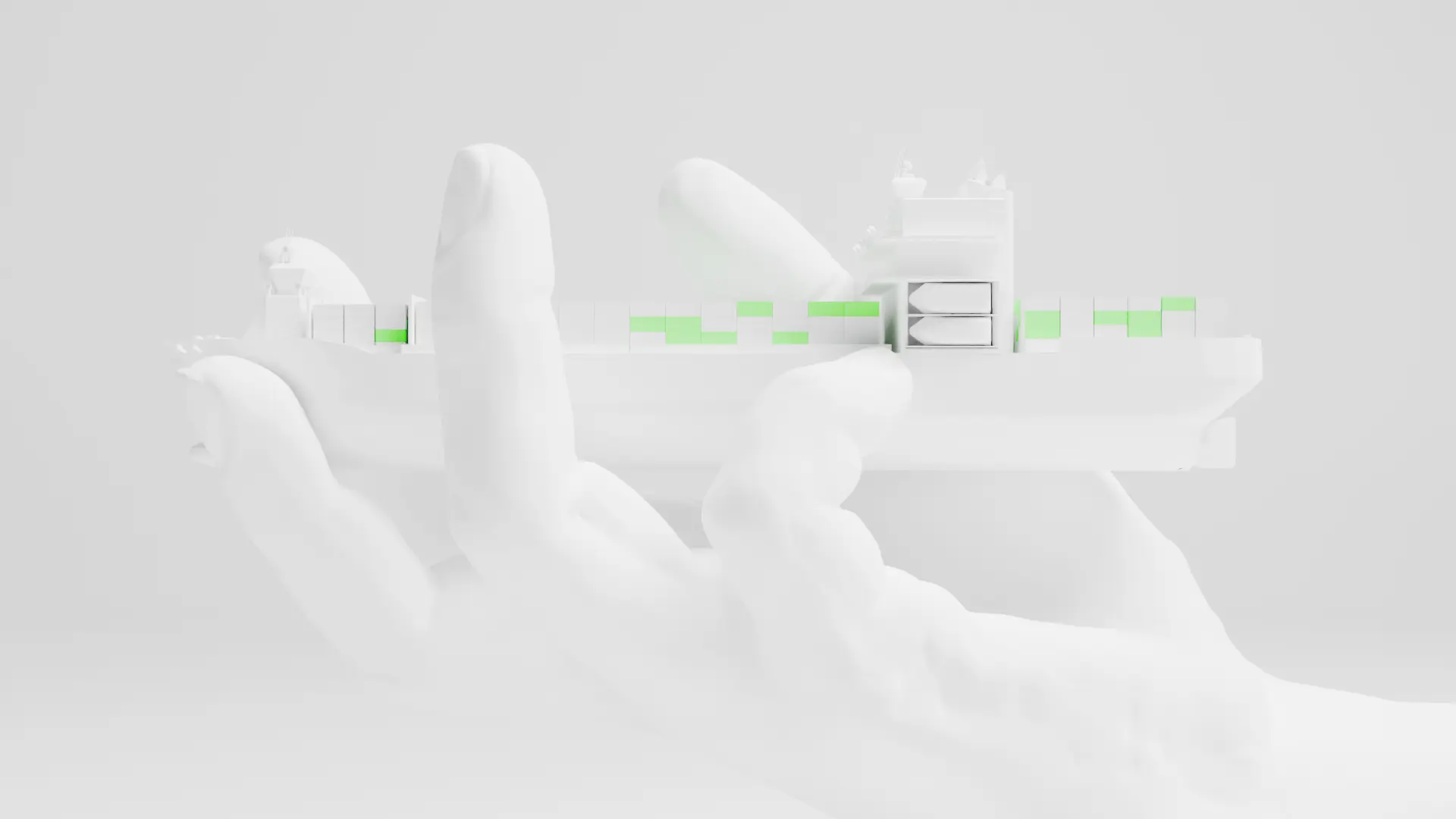

Visuals created by a team member holding an Entrant Visa at Within International.